Highlights

- Crime victimization is both prevalent and costly due to negative short- and long-term outcomes.

- Access to resources and support from victim services providers can help victims through the recovery process after a crime occurs.

- VOCA’s Crime Victims Fund (CVF), financed by offenders, supports victim service providers – but this fund is depleting.

- Breaks and inequities in service access underscore the need for legislative action to support victim service providers and the availability of trauma-informed services.

Over 5.8 million people in the U.S. were victims of violent crime (e.g., domestic violence, sexual assault), in 2019.1 In the same year approximately 678,000 children were victims of abuse or neglect.2 Crime victimization is costly to both victims and society.3,4 The resources victims need are often provided by victim service providers and victim advocate agencies, which heavily rely on funding through the Victims of Crime Act’s (VOCA) Crime Victims Fund (CVF). The CVF is financed by offenders – fines, forfeitures, and penalty assessments on criminal offenders of federally prosecuted crimes – not taxpayers. Through the CVF, states provide the primary funding source for victim services agencies to deliver direct resources and services that victims desperately need. Deposits into the CVF have dropped 86% since 2014 and, to the detriment of victims, the CVF is projected to reach a ten-year low in 2021.5 Steps must be taken to protect victims’ access to essential victim services.

Victim Needs and Service Providers

Being the victim of a crime or witnessing violence are stressful events which can leave victims with unmet essential needs. Prolonged stress can lead to physical (e.g., cancer, diabetes, stroke) and mental health problems (e.g., anxiety, depression) due to problematic health behaviors (e.g., poor nutritional intake, substance use) and chronic overexposure to stress hormones (e.g., cortisol).[6,7] Addressing the varied needs of victims is important for their long-term health and wellbeing.

Victim service providers (VSPs): Offer physical, emotional, and psychological services to victims of crime. In 2018, there were over 6,000 VOCA-funded service providers that assisted 6.3 million crime victims.[8] Examples of services provided to victims include:

- Evidence-based trauma therapies.[a] A lack of mental health services can lead to increased use of costly emergency services for both children and adults.[10,11 When victims of assault are provided with mental health services, symptoms of PTSD, suicide, anxiety, and depression decrease and reports of social support and positive mental health outcomes increase.[12–14]

- Housing assistance. Crime victimization is linked with increased homelessness. Being provided safe, stable housing and receiving temporary financial assistance greatly reduces the likelihood that families enter homeless shelters.[15–18] Rapid rehousing and flexible funding programs enable victims to meet their basic needs.[19]

- Criminal and civil justice system assistance is related to greater safety, psychological well-being, and financial independence for women.[20,21] Receipt of civil protective orders help survivors endure less severe abuse and experience less fear of future harm.[22]

- Advocacy organizations provide critical information about victims’ rights and provide emotional support through accompaniment to law enforcement interviews or forensic medical exams. Accessing healthcare after a sexual assault allows victims to be treated for injury, receive preventive care for infections, and allows for preservation of evidence of the assault which may be key to successful prosecution.[23–25] Alternatively, delayed access to appropriate healthcare can result in increased mental health issues and negative physical health consequences.[26]

a. One example of an evidence-based trauma therapy is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), through which people learn how to improve the effectiveness of their reactions to challenging situations.[9]

Broken Pathways to Service Access

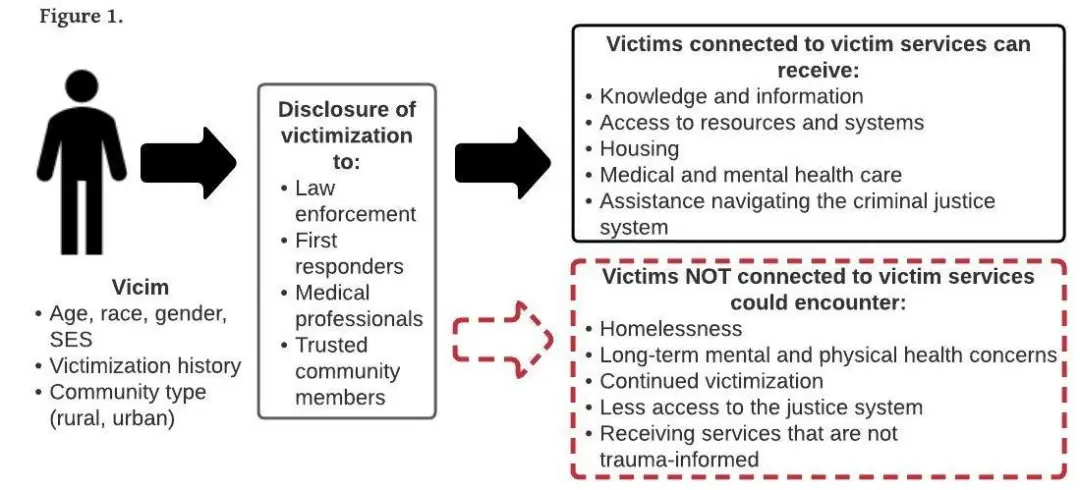

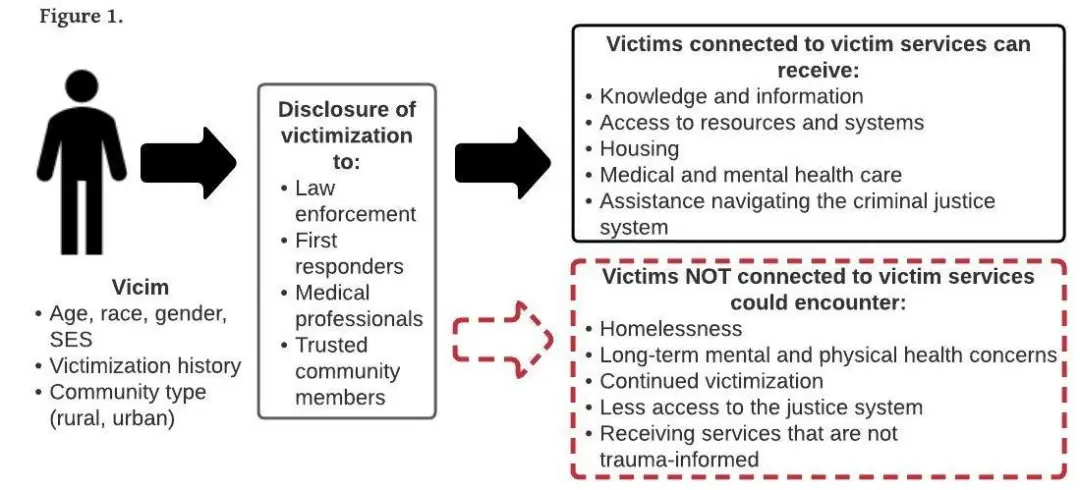

Crime victims seek help and support through various informal (e.g. friends, family) and formal (e.g. advocacy organizations, healthcare, or law enforcement) pathways. Victim characteristics – including race, gender, and age – can impact whether and how victims disclose their victimization and access services.

- U.S. Department of Justice studies estimate that only 23% of sexual assaults are reported to police.[1,27,28] Victims of sexual assault or domestic violence may be reluctant to report to law enforcement due to complex circumstances, especially when the perpetrator is a family member or partner.[29] However, when healthcare services are delivered by a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE; a registered nurse specially trained in sexual assault) or when victim advocacy organizations exist within a community, reports to law enforcement increase, successful prosecution of perpetrators increases, and victims receive more appropriate healthcare and have better mental health outcomes.

- When children are victims of crime (e.g., abused), Child Advocacy Centers (CACs) are essential to the investigative process, providing expert forensic interviews and medical exams in a safe, supportive environment tailored for children. Although the number of CACs across the country are increasing,[30] CACs are not mandatory or accessible in all areas, particularly rural counties.[31]

Victims without access to specialized services provided by VSPs or CACs may receive services that are not trauma informed.[31,32] Ideally, these unique and complimentary services should exist in every community, so victims can get help for their immediate needs, learn about their rights and options, and receive support as they access other services or engage with the justice system. For these reasons, it is essential that victims’ access to multiple pathways to services (see Figure 1) is protected.

Inequities in Access to Services and Care Exist.

Great disparities exist in the quality of care victims receive, depending on whether they live in rural versus urban settings. Rural communities often have limited resources to fuel a comprehensive response to meet the needs of victims and lack of access to specialty healthcare services, such as Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs).[33] Creative solutions are needed to ensure equitable access to quality care and services. A promising example is the use of telehealth to decrease inequities in the quality of forensic sexual assault care in underserved communities by providing expert SANE consultation, interactive mentoring, quality assurance and training to less experienced nurses via telehealth technology.[34,35]

Additional Considerations: Race and Gender.

Lifetime prevalence of domestic violence and sexual assault are highest among women of color, who tend to turn to informal, rather than formal (e.g., VSPs), supports for help.[36] Male victims are also at a disadvantage for accessing services, due to personal reasons (e.g., shame or fear)[37] or a lack of services with a focus on male victims.[38] Individuals who identify as transgender or non-binary are especially at risk for crime victimization[39] but are least likely to access services generally due to lack of knowledge about the services available to them and concern about revictimization and blame.[40] VSPs are often uniquely trained and ready to support these populations but need funding and resources, such as the ability to leverage telehealth, to do so. Without access to these specialized services, inequities in victims’ access to appropriate, trauma-informed services are not addressed.

To Better Serve Victims and Protect the Providers that Assist Them:

- Victim services should be sustained by penalty fees, grant programs, or educating prosecutors on the CVF. Deferred prosecution agreements (DPAs) and non-prosecution agreements (NPAs) are becoming exceedingly prevalent[41] yet funds from them are currently allocated to the General Treasury, not the CVF.

- Consider victims’ access to services when assessing community need and legislative direction. Co-location service models, like the Family Justice Center Alliance, can provide referrals and information for both child and domestic violence victims in one location.[42] An expansion of CACs and inclusion of mobile units could offer additional access to child victims and their families.

- Incentivize the adoption of telehealth models of care for victims of violence. VSPs may help minimize breaks in service access when digitally connected with the appropriate experts (e.g., by working with nurses in settings that are subsidized by the CVF). Telehealth models of care in which regional hubs of expertise facilitate quality healthcare response in under-resourced, rural settings, show promise in growing and sustaining SANE programs.

Recommendations

- Victim services should be sustained by penalty fees, grant programs, or educating prosecutors on the CVF.

- Encourage coordination between first responders and victim service providers.

- Support rural community access to specialized victim services via telehealth.

Resources with Additional Information about VOCA and the CVF

- Office for Victims of Crime: Formula Grants and Victims of Crime Act: Victim Assistance Formula Grant Program

- Sacco, L. N. (2020). The Crime Victims Fund: Federal Support for Victims of Crime (CRS Report No. R42672).

- National Association of VOCA Assistance Administrators

End Notes / References

- Morgan RE, Truman JL. Criminal Victimization, 2019. U.S. Department of Justice; 2020:1-53. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv19.pdf

- Child Maltreatment 2018. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau; 2020:1-274.

- Hanson RF, Sawyer GK, Begle AM, Hubel GS. The impact of crime victimization on quality of life. J Trauma Stress. Published online 2010:n/a-n/a. doi:10.1002/jts.20508

- McCollister KE, French MT, Fang H. The cost of crime to society: New crime-specific estimates for policy and program evaluation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108(1-2):98-109. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.002

- Sacco LN. The Crime Victims Fund: Federal Support for Victims of Crime. Congressional Research Service; 2020:22. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42672

- Mcewen BS. Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators. N Engl J Med. Published online 1998:1-9.

- O’Connor DB, Thayer JF, Vedhara K. Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes. Annu Rev Psychol. 2021;72(1):663-688. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-062520-122331

- Office for Victims of Crime. Victims of Crime Act: Victim Assistance Formula Grant Program. U.S. Department of Justice; 2018:1-10.

- Mayo Clinic. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Mayo Clinic; 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/cognitive-behavioral-therapy/about/pac-20384610

- Buicko JL, Parreco J, Willobee BA, Wagenaar AE, Sola JE. Risk factors for nonelective 30-day readmission in pediatric assault victims. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52(10):1628-1632. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.04.010

- Fleury M-J, Fortin M, Rochette L, et al. Assessing quality indicators related to mental health emergency room utilization. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19(1):1-8. doi:10.1186/s12873-019-0223-8

- Ogbe E, Harmon S, Van den Bergh R, Degomme O. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions focused on improving social support and/ mental health outcomes of survivors. Daoud N, ed. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(6):1-27. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235177

- Guay S, Beaulieu-Prévost D, Sader J, Marchand A. A systematic literature review of early posttraumatic interventions for victims of violent crime. Aggress Violent Behav. 2019;46:15-24. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2019.01.004

- Crespo M, Arinero M. Assessment of the Efficacy of a Psychological Treatment for Women Victims of Violence by their Intimate Male Partner. Span J Psychol. 2010;13(2):849-863. doi:10.1017/S113874160000250X

- Bassuk EL, Volk KT, Olivet J. A Framework for Developing Supports and Services for Families Experiencing Homelessness. Open Health Serv Policy J. 2010;3(2):34-40. doi:10.2174/1874924001003020034

- Padgett DK, Henwood BF, Tsemberis SJ. Housing First: Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives. Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Evans WN, Sullivan JX, Wallskog M. The impact of homelessness prevention programs on homelessness. Science. 2016;353(6300):694-699. doi:10.1126/science.aag0833

- Tsai J. Lifetime and 1-year prevalence of homelessness in the US population: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J Public Health. 2018;40(1):65-74. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdx034

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. Rapid Re-Housing. National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2020. https://endhomelessness.org/ending-homelessness/solutions/rapid-re-housing/

- Hartley CC, Renner LM. The Longer-Term Influence of Civil Legal Services on Battered Women. Published online 2016:1-115.

- Sullivan TP, Weiss NH, Woerner J, Wyatt J, Carey C. Criminal Orders of Protection for Domestic Violence: Associated Revictimization, Mental Health, and Well-being Among Victims. J Interpers Violence. Published online October 28, 2019:1-22. doi:10.1177/0886260519883865

- Rosenberg JS, Grab DA. The Economic Benefits of Providing Civil Legal Assistance to Survivors of Domestic Violence. Inst Policy Integr. Published online 2015:1-34.

- Stewart FH, Trussell J. Prevention of pregnancy resulting from rape: A neglected preventive health measure. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(4):228-229. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00243-9

- A National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations: Adults/Adolescents. U.S. Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women; 2013:144. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ovw/241903.pdf

- Medical Forensic Exam: What Is a Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examination? International Association of Forensic Nurses https://www.safeta.org/page/369

- Lanthier S, Du Mont J, Mason R. Responding to Delayed Disclosure of Sexual Assault in Health Settings: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;19(3):251-265. doi:10.1177/1524838016659484

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. National Incident-Based Reporting System. U.S. Department of Justice; 2019:1-3.

- Reaves BA. Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, 2009 – Statistical Tables. Stat Tables. Published online 2009:40.

- Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P, Weintraub S. A Theoretical Framework for Understanding Help-Seeking Processes Among Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;36(1-2):71-84. doi:10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6

- National Children’s Alliance. One Voice, Stronger: Annual Report 2019. National Children’s Alliance; 2019:1-28. https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/AR2019-web.pdf

- Healing, Justice, & Trust: A National Report on Outcomes for Children’s Advocacy Centers 2019. National Children’s Alliance https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2019-OMS-Brief.pdf

- Ranade R, Wolfe DS, Hao J. Child Advocacy Center Statewide Plan Development: Technical Assistance to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The Field Center for Children’s Policy, Practice, and Research, The University of Pennsylvania; 2014. https://www.pccd.pa.gov/AboutUs/Documents/PCCD%20Report%20Statewide%20CAC%20Plan.pdf

- Thiede E, Miyamoto S. Rural Availability of Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs). J Rural Health. 2021;37(1):81-91. doi:10.1111/jrh.12544

- Miyamoto S, Dharmar M, Boyle C, et al. Impact of telemedicine on the quality of forensic sexual abuse examinations in rural communities. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(9):1533-1539. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.04.015

- Miyamoto S, Thiede E, Dorn L, Perkins DF, Bittner C, Scanlon D. The Sexual Assault Forensic Examination Telehealth (SAFE‐T) Center: A Comprehensive, Nurse‐led Telehealth Model to Address Disparities in Sexual Assault Care. J Rural Health. 2021;37(1):92-102. doi:10.1111/jrh.12474

- Sylaska KM, Edwards KM. Disclosure of Intimate Partner Violence to Informal Social Support Network Members: A Review of the Literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2014;15(1):3-21. doi:10.1177/1524838013496335

- Walker J, Archer J, Davies M. Effects of Rape on Men: A Descriptive Analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34(1):69-80. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-1001-0

- McLean IA. The male victim of sexual assault. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27(1):39-46. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.006

- Logan T, Evans L, Stevenson E, Jordan CE. Barriers to Services for Rural and Urban Survivors of Rape. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20(5):591-616. doi:10.1177/0886260504272899

- Patterson D, Greeson M, Campbell R. Understanding Rape Survivors’ Decisions Not to Seek Help from Formal Social Systems. Health Soc Work. 2009;34(2):127-136. doi:10.1093/hsw/34.2.127

- Larence ER. Corporate Crime: Preliminary Observations on DOJ’s Use and Oversight of Deferred Prosecution and Non-Prosecution Agreements. United States Government Accountability Office; 2009:1-35. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-09-636T

- Family Justice Centers. About Family Justice Centers. Alliance for Hope International; 2020. https://www.familyjusticecenter.org/affiliated-centers/family-justice-centers-2/

The Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC) works to bring together research professionals and public officials to support evidence-based policy. Please visit their website to learn more.

Key Information

RPC Website

Research-to-Policy Collaboration

More RPC Resources

RPC Resources

Publication DateMarch 1, 2021

Topic Area(s)Social Services, Violence and Victimization

Resource TypeWritten Briefs

Share This Page

Highlights

- Crime victimization is both prevalent and costly due to negative short- and long-term outcomes.

- Access to resources and support from victim services providers can help victims through the recovery process after a crime occurs.

- VOCA’s Crime Victims Fund (CVF), financed by offenders, supports victim service providers – but this fund is depleting.

- Breaks and inequities in service access underscore the need for legislative action to support victim service providers and the availability of trauma-informed services.

Over 5.8 million people in the U.S. were victims of violent crime (e.g., domestic violence, sexual assault), in 2019.1 In the same year approximately 678,000 children were victims of abuse or neglect.2 Crime victimization is costly to both victims and society.3,4 The resources victims need are often provided by victim service providers and victim advocate agencies, which heavily rely on funding through the Victims of Crime Act’s (VOCA) Crime Victims Fund (CVF). The CVF is financed by offenders – fines, forfeitures, and penalty assessments on criminal offenders of federally prosecuted crimes – not taxpayers. Through the CVF, states provide the primary funding source for victim services agencies to deliver direct resources and services that victims desperately need. Deposits into the CVF have dropped 86% since 2014 and, to the detriment of victims, the CVF is projected to reach a ten-year low in 2021.5 Steps must be taken to protect victims’ access to essential victim services.

Victim Needs and Service Providers

Being the victim of a crime or witnessing violence are stressful events which can leave victims with unmet essential needs. Prolonged stress can lead to physical (e.g., cancer, diabetes, stroke) and mental health problems (e.g., anxiety, depression) due to problematic health behaviors (e.g., poor nutritional intake, substance use) and chronic overexposure to stress hormones (e.g., cortisol).[6,7] Addressing the varied needs of victims is important for their long-term health and wellbeing.

Victim service providers (VSPs): Offer physical, emotional, and psychological services to victims of crime. In 2018, there were over 6,000 VOCA-funded service providers that assisted 6.3 million crime victims.[8] Examples of services provided to victims include:

- Evidence-based trauma therapies.[a] A lack of mental health services can lead to increased use of costly emergency services for both children and adults.[10,11 When victims of assault are provided with mental health services, symptoms of PTSD, suicide, anxiety, and depression decrease and reports of social support and positive mental health outcomes increase.[12–14]

- Housing assistance. Crime victimization is linked with increased homelessness. Being provided safe, stable housing and receiving temporary financial assistance greatly reduces the likelihood that families enter homeless shelters.[15–18] Rapid rehousing and flexible funding programs enable victims to meet their basic needs.[19]

- Criminal and civil justice system assistance is related to greater safety, psychological well-being, and financial independence for women.[20,21] Receipt of civil protective orders help survivors endure less severe abuse and experience less fear of future harm.[22]

- Advocacy organizations provide critical information about victims’ rights and provide emotional support through accompaniment to law enforcement interviews or forensic medical exams. Accessing healthcare after a sexual assault allows victims to be treated for injury, receive preventive care for infections, and allows for preservation of evidence of the assault which may be key to successful prosecution.[23–25] Alternatively, delayed access to appropriate healthcare can result in increased mental health issues and negative physical health consequences.[26]

a. One example of an evidence-based trauma therapy is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), through which people learn how to improve the effectiveness of their reactions to challenging situations.[9]

Broken Pathways to Service Access

Crime victims seek help and support through various informal (e.g. friends, family) and formal (e.g. advocacy organizations, healthcare, or law enforcement) pathways. Victim characteristics – including race, gender, and age – can impact whether and how victims disclose their victimization and access services.

- U.S. Department of Justice studies estimate that only 23% of sexual assaults are reported to police.[1,27,28] Victims of sexual assault or domestic violence may be reluctant to report to law enforcement due to complex circumstances, especially when the perpetrator is a family member or partner.[29] However, when healthcare services are delivered by a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE; a registered nurse specially trained in sexual assault) or when victim advocacy organizations exist within a community, reports to law enforcement increase, successful prosecution of perpetrators increases, and victims receive more appropriate healthcare and have better mental health outcomes.

- When children are victims of crime (e.g., abused), Child Advocacy Centers (CACs) are essential to the investigative process, providing expert forensic interviews and medical exams in a safe, supportive environment tailored for children. Although the number of CACs across the country are increasing,[30] CACs are not mandatory or accessible in all areas, particularly rural counties.[31]

Victims without access to specialized services provided by VSPs or CACs may receive services that are not trauma informed.[31,32] Ideally, these unique and complimentary services should exist in every community, so victims can get help for their immediate needs, learn about their rights and options, and receive support as they access other services or engage with the justice system. For these reasons, it is essential that victims’ access to multiple pathways to services (see Figure 1) is protected.

Inequities in Access to Services and Care Exist.

Great disparities exist in the quality of care victims receive, depending on whether they live in rural versus urban settings. Rural communities often have limited resources to fuel a comprehensive response to meet the needs of victims and lack of access to specialty healthcare services, such as Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs).[33] Creative solutions are needed to ensure equitable access to quality care and services. A promising example is the use of telehealth to decrease inequities in the quality of forensic sexual assault care in underserved communities by providing expert SANE consultation, interactive mentoring, quality assurance and training to less experienced nurses via telehealth technology.[34,35]

Additional Considerations: Race and Gender.

Lifetime prevalence of domestic violence and sexual assault are highest among women of color, who tend to turn to informal, rather than formal (e.g., VSPs), supports for help.[36] Male victims are also at a disadvantage for accessing services, due to personal reasons (e.g., shame or fear)[37] or a lack of services with a focus on male victims.[38] Individuals who identify as transgender or non-binary are especially at risk for crime victimization[39] but are least likely to access services generally due to lack of knowledge about the services available to them and concern about revictimization and blame.[40] VSPs are often uniquely trained and ready to support these populations but need funding and resources, such as the ability to leverage telehealth, to do so. Without access to these specialized services, inequities in victims’ access to appropriate, trauma-informed services are not addressed.

To Better Serve Victims and Protect the Providers that Assist Them:

- Victim services should be sustained by penalty fees, grant programs, or educating prosecutors on the CVF. Deferred prosecution agreements (DPAs) and non-prosecution agreements (NPAs) are becoming exceedingly prevalent[41] yet funds from them are currently allocated to the General Treasury, not the CVF.

- Consider victims’ access to services when assessing community need and legislative direction. Co-location service models, like the Family Justice Center Alliance, can provide referrals and information for both child and domestic violence victims in one location.[42] An expansion of CACs and inclusion of mobile units could offer additional access to child victims and their families.

- Incentivize the adoption of telehealth models of care for victims of violence. VSPs may help minimize breaks in service access when digitally connected with the appropriate experts (e.g., by working with nurses in settings that are subsidized by the CVF). Telehealth models of care in which regional hubs of expertise facilitate quality healthcare response in under-resourced, rural settings, show promise in growing and sustaining SANE programs.

Recommendations

- Victim services should be sustained by penalty fees, grant programs, or educating prosecutors on the CVF.

- Encourage coordination between first responders and victim service providers.

- Support rural community access to specialized victim services via telehealth.

Resources with Additional Information about VOCA and the CVF

- Office for Victims of Crime: Formula Grants and Victims of Crime Act: Victim Assistance Formula Grant Program

- Sacco, L. N. (2020). The Crime Victims Fund: Federal Support for Victims of Crime (CRS Report No. R42672).

- National Association of VOCA Assistance Administrators

End Notes / References

- Morgan RE, Truman JL. Criminal Victimization, 2019. U.S. Department of Justice; 2020:1-53. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv19.pdf

- Child Maltreatment 2018. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau; 2020:1-274.

- Hanson RF, Sawyer GK, Begle AM, Hubel GS. The impact of crime victimization on quality of life. J Trauma Stress. Published online 2010:n/a-n/a. doi:10.1002/jts.20508

- McCollister KE, French MT, Fang H. The cost of crime to society: New crime-specific estimates for policy and program evaluation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108(1-2):98-109. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.002

- Sacco LN. The Crime Victims Fund: Federal Support for Victims of Crime. Congressional Research Service; 2020:22. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42672

- Mcewen BS. Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators. N Engl J Med. Published online 1998:1-9.

- O’Connor DB, Thayer JF, Vedhara K. Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes. Annu Rev Psychol. 2021;72(1):663-688. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-062520-122331

- Office for Victims of Crime. Victims of Crime Act: Victim Assistance Formula Grant Program. U.S. Department of Justice; 2018:1-10.

- Mayo Clinic. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Mayo Clinic; 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/cognitive-behavioral-therapy/about/pac-20384610

- Buicko JL, Parreco J, Willobee BA, Wagenaar AE, Sola JE. Risk factors for nonelective 30-day readmission in pediatric assault victims. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52(10):1628-1632. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.04.010

- Fleury M-J, Fortin M, Rochette L, et al. Assessing quality indicators related to mental health emergency room utilization. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19(1):1-8. doi:10.1186/s12873-019-0223-8

- Ogbe E, Harmon S, Van den Bergh R, Degomme O. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions focused on improving social support and/ mental health outcomes of survivors. Daoud N, ed. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(6):1-27. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235177

- Guay S, Beaulieu-Prévost D, Sader J, Marchand A. A systematic literature review of early posttraumatic interventions for victims of violent crime. Aggress Violent Behav. 2019;46:15-24. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2019.01.004

- Crespo M, Arinero M. Assessment of the Efficacy of a Psychological Treatment for Women Victims of Violence by their Intimate Male Partner. Span J Psychol. 2010;13(2):849-863. doi:10.1017/S113874160000250X

- Bassuk EL, Volk KT, Olivet J. A Framework for Developing Supports and Services for Families Experiencing Homelessness. Open Health Serv Policy J. 2010;3(2):34-40. doi:10.2174/1874924001003020034

- Padgett DK, Henwood BF, Tsemberis SJ. Housing First: Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives. Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Evans WN, Sullivan JX, Wallskog M. The impact of homelessness prevention programs on homelessness. Science. 2016;353(6300):694-699. doi:10.1126/science.aag0833

- Tsai J. Lifetime and 1-year prevalence of homelessness in the US population: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J Public Health. 2018;40(1):65-74. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdx034

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. Rapid Re-Housing. National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2020. https://endhomelessness.org/ending-homelessness/solutions/rapid-re-housing/

- Hartley CC, Renner LM. The Longer-Term Influence of Civil Legal Services on Battered Women. Published online 2016:1-115.

- Sullivan TP, Weiss NH, Woerner J, Wyatt J, Carey C. Criminal Orders of Protection for Domestic Violence: Associated Revictimization, Mental Health, and Well-being Among Victims. J Interpers Violence. Published online October 28, 2019:1-22. doi:10.1177/0886260519883865

- Rosenberg JS, Grab DA. The Economic Benefits of Providing Civil Legal Assistance to Survivors of Domestic Violence. Inst Policy Integr. Published online 2015:1-34.

- Stewart FH, Trussell J. Prevention of pregnancy resulting from rape: A neglected preventive health measure. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(4):228-229. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00243-9

- A National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations: Adults/Adolescents. U.S. Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women; 2013:144. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ovw/241903.pdf

- Medical Forensic Exam: What Is a Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examination? International Association of Forensic Nurses https://www.safeta.org/page/369

- Lanthier S, Du Mont J, Mason R. Responding to Delayed Disclosure of Sexual Assault in Health Settings: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;19(3):251-265. doi:10.1177/1524838016659484

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. National Incident-Based Reporting System. U.S. Department of Justice; 2019:1-3.

- Reaves BA. Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, 2009 – Statistical Tables. Stat Tables. Published online 2009:40.

- Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P, Weintraub S. A Theoretical Framework for Understanding Help-Seeking Processes Among Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;36(1-2):71-84. doi:10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6

- National Children’s Alliance. One Voice, Stronger: Annual Report 2019. National Children’s Alliance; 2019:1-28. https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/AR2019-web.pdf

- Healing, Justice, & Trust: A National Report on Outcomes for Children’s Advocacy Centers 2019. National Children’s Alliance https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2019-OMS-Brief.pdf

- Ranade R, Wolfe DS, Hao J. Child Advocacy Center Statewide Plan Development: Technical Assistance to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The Field Center for Children’s Policy, Practice, and Research, The University of Pennsylvania; 2014. https://www.pccd.pa.gov/AboutUs/Documents/PCCD%20Report%20Statewide%20CAC%20Plan.pdf

- Thiede E, Miyamoto S. Rural Availability of Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs). J Rural Health. 2021;37(1):81-91. doi:10.1111/jrh.12544

- Miyamoto S, Dharmar M, Boyle C, et al. Impact of telemedicine on the quality of forensic sexual abuse examinations in rural communities. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(9):1533-1539. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.04.015

- Miyamoto S, Thiede E, Dorn L, Perkins DF, Bittner C, Scanlon D. The Sexual Assault Forensic Examination Telehealth (SAFE‐T) Center: A Comprehensive, Nurse‐led Telehealth Model to Address Disparities in Sexual Assault Care. J Rural Health. 2021;37(1):92-102. doi:10.1111/jrh.12474

- Sylaska KM, Edwards KM. Disclosure of Intimate Partner Violence to Informal Social Support Network Members: A Review of the Literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2014;15(1):3-21. doi:10.1177/1524838013496335

- Walker J, Archer J, Davies M. Effects of Rape on Men: A Descriptive Analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34(1):69-80. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-1001-0

- McLean IA. The male victim of sexual assault. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27(1):39-46. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.006

- Logan T, Evans L, Stevenson E, Jordan CE. Barriers to Services for Rural and Urban Survivors of Rape. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20(5):591-616. doi:10.1177/0886260504272899

- Patterson D, Greeson M, Campbell R. Understanding Rape Survivors’ Decisions Not to Seek Help from Formal Social Systems. Health Soc Work. 2009;34(2):127-136. doi:10.1093/hsw/34.2.127

- Larence ER. Corporate Crime: Preliminary Observations on DOJ’s Use and Oversight of Deferred Prosecution and Non-Prosecution Agreements. United States Government Accountability Office; 2009:1-35. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-09-636T

- Family Justice Centers. About Family Justice Centers. Alliance for Hope International; 2020. https://www.familyjusticecenter.org/affiliated-centers/family-justice-centers-2/

The Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC) works to bring together research professionals and public officials to support evidence-based policy. Please visit their website to learn more.

Key Information

RPC Website

Research-to-Policy Collaboration

More RPC Resources

RPC Resources

Publication DateMarch 1, 2021

Topic Area(s)Social Services, Violence and Victimization

Resource TypeWritten Briefs

Share This Page

LET’S STAY IN TOUCH

Join the Evidence-to-Impact Mailing List

Keep up to date with the latest resources, events, and news from the EIC.