Sexual violence affects huge swaths of the population – both adults and children – and has long-term impacts on survivors’ emotional, physical, and financial well-being. Survivors benefit from access to immediate and long-term physical and mental healthcare and legal advocacy. Research sheds light on the dynamics of sexual violence, supporting victims, and preventing and reducing sexual violence.

Frequency of Sexual Violence

Lifetime victimization:

- 1 in 4 women (26.8% or 33.5 million) and 1 in 26 men (3.8% or 4.5 million) report that they experienced completed or attempted rape victimization at some point in their lifetime.[1] Other forms of sexual violence, such as sexual coercion and sexual assault, are much more common.[1]

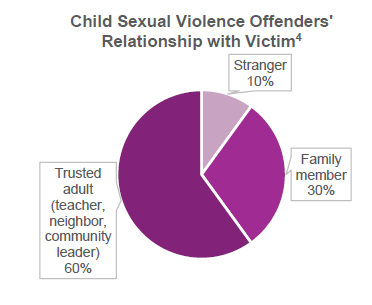

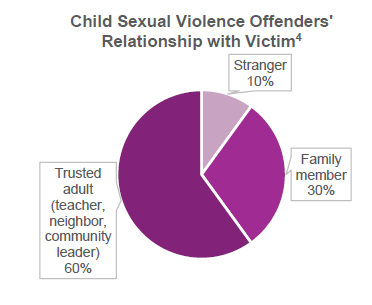

- In the majority of cases with female victims, an offender was an acquaintance (56%) or intimate partner (39%), though offenders are also frequently family members, strangers and brief encounters, and people of authority.

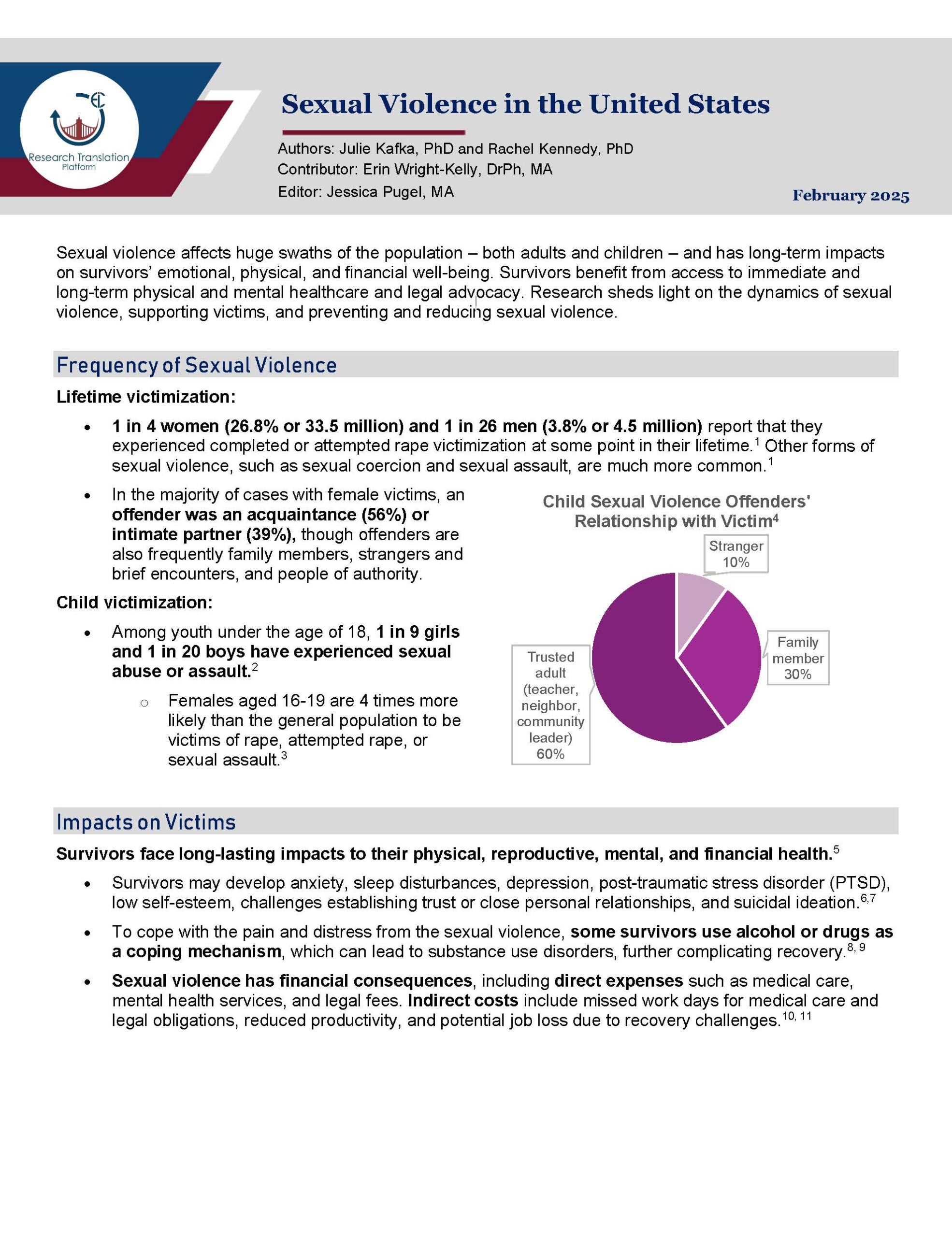

Child victimization:

- Among youth under the age of 18, 1 in 9 girls and 1 in 20 boys have experienced sexual abuse or assault.[2]

- Females aged 16-19 are 4 times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault.[3]

Impacts on Victims

Survivors face long-lasting impacts to their physical, reproductive, mental, and financial health.[5]

- Survivors may develop anxiety, sleep disturbances, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), low self-esteem, challenges establishing trust or close personal relationships, and suicidal ideation.[6,7]

- To cope with the pain and distress from the sexual violence, some survivors use alcohol or drugs as a coping mechanism, which can lead to substance use disorders, further complicating recovery.[8, 9]

- Sexual violence has financial consequences, including direct expenses such as medical care, mental health services, and legal fees. Indirect costs include missed work days for medical care and legal obligations, reduced productivity, and potential job loss due to recovery challenges.[10, 11]

Reporting and Justice

Sex crimes are the most under-reported crimes, with 63% of sexual assaults not being reported to police.[12] Many survivors do not report what happened given fear or intimidation by the perpetrator, stigma, humiliation, or challenges faced while reporting.

- When sexual assault is reported, only a small proportion of cases result in a conviction.[13]

- Access to legal advocates and/or representation may improve case completion rates but, for many survivors, the choice not to pursue a court case may benefit their mental health.[14]

Supporting Victims in the Short- and Long-Term

Addressing immediate health concerns:

- It is critical that the victim has access to trained forensic nurses to provide medical treatment, support reproductive healthcare, and collect physical evidence.

- Access to abortions for rape victims may improve their physical and mental health outcomes, including support to navigate abortion bans with exceptions to rape.

Navigating safety and reporting:

- Survivors rely on law enforcement, healthcare workers, and advocates to help navigate reporting options (medical, law, anonymous) and empower them to decide their best path for their justice and healing. Thus, regular training of these employees is beneficial.

- Best practices suggest that screening for sexual violence should be trauma-informed, and survivors must be able to maintain control in deciding next steps if they choose to report.[7]

- Empowering, non-judgmental messaging encourages reporting and response.

Accessing counseling and financial support:

- Community-based organizations (e.g., Three Birds Alliance, The Blue Bench, Rose Andom Center) provide comprehensive services that help survivors gain treatment, access and navigate legal resources, and ultimately heal. Some operate using the Family Justice Center model, where services and staff from several agencies are co-located in one central place.

- Mental health treatment, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, integrative therapies, and psychosocial interventions, can significantly decrease PTSD and depression symptoms.[15]

- Victim compensation funds are an important source of financial support, although it is likely that only a minority of victims gain access to these funds.[13]

Preventing Sexual Violence [16, 17, 18]

- Educate young children and parents about risks related to online predation (e.g., grooming, cyber-harassment) and the promotion of healthy dating relationships for adolescents.

- Bystander trainings can help friends and other parties identify warning signs for sexual violence and gain the skills and confidence needed to intervene.

- Changing cultural norms to reject beliefs that objectify women and girls, trivialize or endorse rape, and blame survivors can help raise awareness, prevent sexual violence, and encourage healing.

- Adequately train healthcare providers, first responders, law enforcement officers, and courtroom professionals to recognize the dynamics and warning signs of sexual violence so that they can be positioned to intervene.

References

- Basile KC, Smith SG, Kresnow M, S. K, Leemis RW. The National Intimate Partnerand Sexual Violence Survey:2016/2017 Report on Sexual Violence. 2022.

- Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner HA, Hamby SL. The lifetime prevalence of child sexual abuse and sexual assault assessed in late adolescence. Journal of adolescent Health. 2014;55(3):329-333.

- Greenfeld LA. Sex offenses and offenders: An analysis of data on rape and sexual assault. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 1997.

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(7):614-621.

- Jina, R., & Thomas, L. S. (2013). Health consequences of sexual violence against women. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology, 27(1), 15-26.

- Dworkin ER. Risk for mental disorders associated with sexual assault: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2020;21(5):1011-1028.

- Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Bacchus, L. J., Astbury, J., & Watts, C. H. (2014). Childhood sexual abuse and suicidal behavior: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 133(5), e1331-e1344.

- Clark, H. Westley, Carmen L. Masson, Kevin L. Delucchi, Sharon M. Hall, and Karen L. Sees. 2001. “Violent Traumatic Events and Drug Use Severity.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 20(2): pp. 121-127.

- Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape, 2009. “Substance Use and Sexual Violence Building Prevention and Intervention Responses.” Retrieved from: https://www.pcar.org/sites/default/files/pages-pdf/substance_use_and_sexual_violence.pdf

- Loya, R. M. (2015). Rape as an economic crime: The impact of sexual violence on survivors’ employment and economic well-being. Journal of interpersonal violence, 30(16), 2793-2813.

- Letourneau, E. J., Brown, D. S., Fang, X., Hassan, A., & Mercy, J. A. (2018). The economic burden of child sexual abuse in the United States. Child abuse & neglect, 79, 413-422.

- Rennison CM. Rape and sexual assault: Reporting to police and medical attention, 1992-2000. 2002;

- Hoffman EE, Patton E, Greeson MR. A Systematic Review of Sexual Assault Case Attrition in the United States from 2000 to 2020. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2024:15248380241293803.

- Asadi L, Noroozi M, Mardani F, Salimi H, Jambarsang S. The needs of women survivors of rape: a narrative review. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research. 2023;28(6):633-641.

- Brown SJ, Khasteganan N, Brown K, et al. Psychosocial interventions for survivors of rape and sexual assault experienced during adulthood. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;2019(11)

- Breger, M. L. (2014). Transforming cultural norms of sexual violence against women. Journal of Research in Gender Studies, 4(2), 39-51.

- World Health Organization (2009). Changing cultural and social norms that support violence. Retrieved from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44147/9789241598330_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Dworkin, E. R., & Weaver, T. L. (2021). The impact of sociocultural contexts on mental health following sexual violence: A conceptual model. Psychology of Violence, 11(5), 476.

The Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC) works to bring together research professionals and public officials to support evidence-based policy. Please visit their website to learn more.

Key Information

RPC Website

Research-to-Policy Collaboration

Publication DateFebruary 21, 2025

Topic Area(s)Violence and Victimization

Resource TypeWritten Briefs

Share This Page

Sexual violence affects huge swaths of the population – both adults and children – and has long-term impacts on survivors’ emotional, physical, and financial well-being. Survivors benefit from access to immediate and long-term physical and mental healthcare and legal advocacy. Research sheds light on the dynamics of sexual violence, supporting victims, and preventing and reducing sexual violence.

Frequency of Sexual Violence

Lifetime victimization:

- 1 in 4 women (26.8% or 33.5 million) and 1 in 26 men (3.8% or 4.5 million) report that they experienced completed or attempted rape victimization at some point in their lifetime.[1] Other forms of sexual violence, such as sexual coercion and sexual assault, are much more common.[1]

- In the majority of cases with female victims, an offender was an acquaintance (56%) or intimate partner (39%), though offenders are also frequently family members, strangers and brief encounters, and people of authority.

Child victimization:

- Among youth under the age of 18, 1 in 9 girls and 1 in 20 boys have experienced sexual abuse or assault.[2]

- Females aged 16-19 are 4 times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault.[3]

Impacts on Victims

Survivors face long-lasting impacts to their physical, reproductive, mental, and financial health.[5]

- Survivors may develop anxiety, sleep disturbances, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), low self-esteem, challenges establishing trust or close personal relationships, and suicidal ideation.[6,7]

- To cope with the pain and distress from the sexual violence, some survivors use alcohol or drugs as a coping mechanism, which can lead to substance use disorders, further complicating recovery.[8, 9]

- Sexual violence has financial consequences, including direct expenses such as medical care, mental health services, and legal fees. Indirect costs include missed work days for medical care and legal obligations, reduced productivity, and potential job loss due to recovery challenges.[10, 11]

Reporting and Justice

Sex crimes are the most under-reported crimes, with 63% of sexual assaults not being reported to police.[12] Many survivors do not report what happened given fear or intimidation by the perpetrator, stigma, humiliation, or challenges faced while reporting.

- When sexual assault is reported, only a small proportion of cases result in a conviction.[13]

- Access to legal advocates and/or representation may improve case completion rates but, for many survivors, the choice not to pursue a court case may benefit their mental health.[14]

Supporting Victims in the Short- and Long-Term

Addressing immediate health concerns:

- It is critical that the victim has access to trained forensic nurses to provide medical treatment, support reproductive healthcare, and collect physical evidence.

- Access to abortions for rape victims may improve their physical and mental health outcomes, including support to navigate abortion bans with exceptions to rape.

Navigating safety and reporting:

- Survivors rely on law enforcement, healthcare workers, and advocates to help navigate reporting options (medical, law, anonymous) and empower them to decide their best path for their justice and healing. Thus, regular training of these employees is beneficial.

- Best practices suggest that screening for sexual violence should be trauma-informed, and survivors must be able to maintain control in deciding next steps if they choose to report.[7]

- Empowering, non-judgmental messaging encourages reporting and response.

Accessing counseling and financial support:

- Community-based organizations (e.g., Three Birds Alliance, The Blue Bench, Rose Andom Center) provide comprehensive services that help survivors gain treatment, access and navigate legal resources, and ultimately heal. Some operate using the Family Justice Center model, where services and staff from several agencies are co-located in one central place.

- Mental health treatment, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, integrative therapies, and psychosocial interventions, can significantly decrease PTSD and depression symptoms.[15]

- Victim compensation funds are an important source of financial support, although it is likely that only a minority of victims gain access to these funds.[13]

Preventing Sexual Violence [16, 17, 18]

- Educate young children and parents about risks related to online predation (e.g., grooming, cyber-harassment) and the promotion of healthy dating relationships for adolescents.

- Bystander trainings can help friends and other parties identify warning signs for sexual violence and gain the skills and confidence needed to intervene.

- Changing cultural norms to reject beliefs that objectify women and girls, trivialize or endorse rape, and blame survivors can help raise awareness, prevent sexual violence, and encourage healing.

- Adequately train healthcare providers, first responders, law enforcement officers, and courtroom professionals to recognize the dynamics and warning signs of sexual violence so that they can be positioned to intervene.

References

- Basile KC, Smith SG, Kresnow M, S. K, Leemis RW. The National Intimate Partnerand Sexual Violence Survey:2016/2017 Report on Sexual Violence. 2022.

- Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner HA, Hamby SL. The lifetime prevalence of child sexual abuse and sexual assault assessed in late adolescence. Journal of adolescent Health. 2014;55(3):329-333.

- Greenfeld LA. Sex offenses and offenders: An analysis of data on rape and sexual assault. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 1997.

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(7):614-621.

- Jina, R., & Thomas, L. S. (2013). Health consequences of sexual violence against women. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology, 27(1), 15-26.

- Dworkin ER. Risk for mental disorders associated with sexual assault: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2020;21(5):1011-1028.

- Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Bacchus, L. J., Astbury, J., & Watts, C. H. (2014). Childhood sexual abuse and suicidal behavior: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 133(5), e1331-e1344.

- Clark, H. Westley, Carmen L. Masson, Kevin L. Delucchi, Sharon M. Hall, and Karen L. Sees. 2001. “Violent Traumatic Events and Drug Use Severity.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 20(2): pp. 121-127.

- Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape, 2009. “Substance Use and Sexual Violence Building Prevention and Intervention Responses.” Retrieved from: https://www.pcar.org/sites/default/files/pages-pdf/substance_use_and_sexual_violence.pdf

- Loya, R. M. (2015). Rape as an economic crime: The impact of sexual violence on survivors’ employment and economic well-being. Journal of interpersonal violence, 30(16), 2793-2813.

- Letourneau, E. J., Brown, D. S., Fang, X., Hassan, A., & Mercy, J. A. (2018). The economic burden of child sexual abuse in the United States. Child abuse & neglect, 79, 413-422.

- Rennison CM. Rape and sexual assault: Reporting to police and medical attention, 1992-2000. 2002;

- Hoffman EE, Patton E, Greeson MR. A Systematic Review of Sexual Assault Case Attrition in the United States from 2000 to 2020. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2024:15248380241293803.

- Asadi L, Noroozi M, Mardani F, Salimi H, Jambarsang S. The needs of women survivors of rape: a narrative review. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research. 2023;28(6):633-641.

- Brown SJ, Khasteganan N, Brown K, et al. Psychosocial interventions for survivors of rape and sexual assault experienced during adulthood. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;2019(11)

- Breger, M. L. (2014). Transforming cultural norms of sexual violence against women. Journal of Research in Gender Studies, 4(2), 39-51.

- World Health Organization (2009). Changing cultural and social norms that support violence. Retrieved from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44147/9789241598330_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Dworkin, E. R., & Weaver, T. L. (2021). The impact of sociocultural contexts on mental health following sexual violence: A conceptual model. Psychology of Violence, 11(5), 476.

The Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC) works to bring together research professionals and public officials to support evidence-based policy. Please visit their website to learn more.

Key Information

RPC Website

Research-to-Policy Collaboration

Publication DateFebruary 21, 2025

Topic Area(s)Violence and Victimization

Resource TypeWritten Briefs

Share This Page

LET’S STAY IN TOUCH

Join the Evidence-to-Impact Mailing List

Keep up to date with the latest resources, events, and news from the EIC.