This brief provides a closer look at using evidence in the contracting process, one strategy identified in “A Guide to Evidence-Based Budget Development,” a 2016 brief.

Overview

State and local governments frequently rely on community-based organizations to serve individuals and families. In 2012, according to the Urban Institute, governments spent approximately $80 billion through contracts or grants on human services programs that were delivered by nonprofit organizations. Given the critical role these organizations play in assisting vulnerable populations, policymakers should take steps to ensure that whenever possible, funds are invested in programs and services that are proved to work. One promising strategy government leaders can use is to incorporate evidence requirements into their contracting and grant processes.

Increasingly, policymakers recognize that they can improve outcomes, strengthen accountability, and reduce costs by using rigorous evidence to inform choices about which services should be supported with public funds. This issue brief profiles four jurisdictions that are using evidence-based contracting to significantly increase the number of people reached by proven, effective programs: Georgia (child welfare), Florida (juvenile justice), New York (substance abuse), and Santa Cruz County, California (criminal justice).

In developing a system that supports evidence-based contracting, policymakers will want to:

- Use data and research to identify needs and incorporate them into the requirements. In developing the grant and contract language, staff should use data from community needs assessments or similar processes to identify the evidence-based programs that address those needs and have been shown to be effective in achieving the desired outcomes in a given population.

- Work closely with provider organizations throughout the process. Agencies should work closely with community-based providers, county governments, or local health clinics to build support for and understanding of evidence-based principles before issuing grant announcements or embedding requirements in contracts.

- Define criteria for “evidence-based” and be specific in grant announcements. Within state and local governments, there is often significant uncertainty as to what constitutes an evidence-based program. Creating formal definitions of evidence and embedding these definitions in contracts will help clarify expectations of provider organizations and government officials. When feasible, contracts should specify sources, such as nationally recognized research clearinghouses, where providers can find information on a wide range of programs that meet a given standard.

- Build mechanisms into the grants to monitor implementation fidelity and outcomes. A large body of research shows that well-designed programs that are implemented without fidelity to their treatment model are unlikely to achieve the outcomes policymakers and taxpayers expect. As part of their contract requirements, providers should be compelled to report on interim outcomes that are correlated with effective program delivery, in addition to long-term outcomes. Government agencies should direct resources to carefully monitor these efforts.

Case studies

Georgia

- Agency: Office of Prevention and Family Support (OPFS), Division of Family and Children Services.

- Policy area: child welfare.

- Number of providers: 100.

- Total funding for grants/contracts: approximately $9.1 million in calendar year 2014.

- Funding for evidence-based programs: 100 percent of direct service prevention program providers within OPFS are required to offer evidence-based programming.

The Georgia OPFS requires that all contracted prevention services—including family preservation, child abuse prevention, and family support and coaching (home visiting)—utilize evidence-based approaches that meet specified criteria. OPFS works with community-based organizations to promote the safety and well-being of families at risk of entering the child welfare system. Before the office was created in the late 1990s, the state Children’s Trust Fund promoted evidence-based programs through home visiting grants and other prevention programs. In 2014, Governor Nathan Deal (R) created OPFS to administer grants initially operated through the trust fund, as well as other prevention funding sources, and provide training and technical assistance to support community-based organizations delivering child maltreatment prevention activities.

The strategy—to use grant-making as a mechanism for increasing the use of effective evidence-based programs and thereby improving outcomes for Georgia’s children and families—has changed over time. Now the office identifies clear criteria for the level of evidence that programs must meet to be considered for funding, but it also gives providers more flexibility to choose among programs that meet those criteria.

Initially, the office issued requests for proposals that required grantees to implement specified evidence-based program models (selected from several evidence-based registries). Although this method was successful in encouraging community-based organizations to begin implementing such programs, the approach offered few program alternatives and therefore limited providers’ ability to deliver services that would meet the needs of diverse populations.

To address this limitation, the office now distributes funding, including state and federal grants, to provide a wider menu of evidence-based options. Communities can choose the best program to address specific needs as long as the intervention meets the evidence standards. For example, the Division of Family and Children Services recently released, under OPFS, a statement of need for the Promoting Safe and Stable Families program that included eight core evidence-based models from which providers could choose, as well as 33 other evidence-based practices that could be selected based upon specific community needs.3 (Box 1) Another grant opportunity for family support and coaching services identified five models that meet the minimum evidence requirement, based on criteria developed by the California Child Welfare Clearinghouse or other evidence-based registries. “Slowly but surely [through our contracting process] we are implementing evidence-based programs in all categories of primary and secondary prevention in the state,” said Carole Steele, OPFS director.4

State leaders are also taking steps to ensure that these programs achieve expected outcomes by building requirements into contracts for outcome reporting, training, and monitoring program implementation. OPFS requires service provider organizations to work with program developers (the organizations or individuals who generate and license a particular model program) to access training and other supports as part of their contract. “Requiring this close communication has helped build capacity and ensure success for these provider agencies,” Steele said. The state also has some capacity to support the training and implementation needs of providers if program developers are not available. For example, for two evidence-based models—Parents as Teachers and Healthy Families America—the state provides its own training and technical assistance through a contract with the Center for Family Research at the University of Georgia. This ensures that providers are equipped with the training necessary to implement the program as originally intended and achieve expected outcomes.

“Slowly but surely [through our contracting process] we are implementing evidence-based programs in all categories of primary and secondary prevention in the state.”

Carole Steele, director, Georgia Office of Prevention and Family Support

Moving forward, OPFS plans to continue to embed evidence requirements in its contracting processes, with the possibility of expansion throughout the state’s Division of Family and Children Services. However, a number of challenges stand in the way of expansion, including the limited number of providers with sufficient capacity to implement and monitor evidence-based programs. “We don’t have a huge pool of service providers in Georgia that are able to provide evidence-based services. We have to build that capacity across the state and at the same time try to help children remain safely in their homes,” said Steele.

Another key challenge involves educating providers on the value of implementing programs that have been rigorously tested and found effective, particularly when this involves replacing a program that may be underperforming. OPFS staff noted that providers often have a limited amount of funding allocated for prevention services and may be reluctant to choose an evidence-based model that may require additional costs, such as training and data reporting. OPFS meets regularly with providers throughout the state, including holding bidders conferences, where it can share research findings that clearly show how children and families it serves can benefit from these proven effective programs.

Box 1: Georgia Has Established Criteria in Contracts for Funding Evidence-Based Programs

The following is excerpted from the Promoting Safe and Stable Families Program: FFY2017 Statement of Need (SoN) by the Georgia Division of Family and Children Services:

The CEBC [California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse] is a key tool for identifying, selecting, and implementing evidence-based child welfare practices that will improve child safety, increase permanency, increase family and community stability, and promote child and family well-being. … [Promoting Safe and Stable Families] has chosen to use the CEBC scientific rating scale to set its standard for eligible evidence-based strategies, practices or program models required for all FFY2017 proposals. In addition to demonstrating its effectiveness in meeting the objectives for the selected service model, proposed evidence-based strategies, practices or program models must have a medium to high relevance to child welfare, and have been rated:

- —Well-Supported by Research Evidence,

- —Supported by Research Evidence, or

- —Promising Research Evidence by the CEBC.

Florida

-

- Agency: Department of Juvenile Justice.

- Policy area: juvenile justice.

- Number of providers: 142.

- Total funding for grants/contracts: approximately $257 million in state fiscal year 2015-16.

- Funding for evidence-based programs (EBP): 100 percent of delinquency intervention program providers must operate at least one EBP.

The Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) requires that all contracted providers of delinquency prevention programs (including some for-profit organizations) operate at least one evidence-based model, and the department regularly monitors providers to ensure implementation fidelity. To provide effective oversight of these providers, DJJ has developed a robust system for monitoring the implementation of evidence-based programs over the past two decades. The Office of Program Accountability monitors contracted providers using real-time data uploaded into its Juvenile Justice Information System, which shows whether a program is being implemented with fidelity to its model.5 DJJ also provides technical assistance for providers to support training on evidence-based program models.

The department has gradually increased the evidence-based intervention requirements for its contracted providers. Initially it created incentives for providers to offer interventions shown through rigorous research to be effective, giving preference or higher ratings for proposals that included these efforts. Now, all contracts require providers to deliver at least one evidence-based program, although many organizations offer more. To help providers identify which programs to implement, the department created three tiers of evidence—evidence-based (the highest standard), promising, and practices with demonstrated effectiveness—along with an updated list of delinquency interventions that meet each standard. Department staff meet regularly with providers to discuss the contracting requirements, review data used to measure their performance, and gather feedback on ways to improve the process. “We really see our provider organizations as partners,” said Amy Johnson, director of the Office of Program Accountability. “We are a heavily privatized system, and we rely on them to deliver effective services to the population we serve.”6

Box 2: Florida Has Created an Internal Resource for Contracted Providers to Identify Appropriate Evidence-Based Interventions

The Florida Department of Juvenile Justice created A Sourcebook of Delinquency Interventions in 2008 to give providers in the state guidance on which programs aimed at reducing recidivism had been rigorously tested.* The department updated the report in 2011 and 2015, adding several programs and reclassifying others based on updated research on their effectiveness.

The 2015 guide includes 38 programs that meet the evidence criteria. In addition to ranking programs based on the extent to which they had been rigorously evaluated, each intervention lists supplemental information including the target population served, treatment setting, training and certification requirements, and fidelity tools available to monitor the program.

* Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, A Sourcebook of Delinquency Interventions (2015), http://www.djj.state.fl.us/ docs/quality-improvement/sourcebook2015.pdf?sfvrsn=4.

“We have started to monitor more closely the specific interventions being delivered to youth, along with the quality of implementation. We were surprised to find that some of the interventions being implemented were not really based on an evidence-based model.”

Amy Johnson, director, Florida Office of Program Accountability

Over time, department leaders have learned the value of having a contract monitoring system that focuses not only on compliance, but also on ensuring that providers are implementing programs with fidelity to their models. The department uses the Standardized Program Evaluation Protocol to determine how closely programs being implemented in the field align with the features of the most effective programs. The office uses the assessment as both an accountability tool and a way to direct resources to help providers.

Other contract monitoring functions have been automated to improve oversight of service delivery. For example, every youth who participates in a delinquency intervention is now followed in the Juvenile Justice Information System, with data tracking the intensity and duration of those services and whether the youth completed the program, all of which is required as part of the contract. “One significant shift from prior years is that we have started to monitor more closely the specific interventions being delivered to youth, along with the quality of implementation,” said Johnson. “We were surprised to find that some of the interventions being implemented were not really based on an evidence-based model.”

Over time, providers have improved the extent to which they are implementing evidence-based programs with fidelity, based on their Standardized Program Evaluation Protocol scores. While the impact of investing in evidence-based programs may take years to accurately determine, Johnson noted that this was a strong indicator that contracted programs are likely to achieve the outcomes that research has predicted.

New York

- Agency: Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services.

- Policy area: substance abuse prevention.

- Number of providers (prevention): 165.

- Total funding for grants/contracts: approximately $71 million for state fiscal year 2016-17.

- Funding for evidence-based programs: increasing to 70 percent of state funding to contracted providers by 2018.

The New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS) established provider guidelines that require contracted organizations to dedicate an increasing percentage of state funding toward evidence-based programs and strategies. OASAS provides a continuum of services in prevention, treatment, and recovery settings. Many of these services are contracted out to nonprofit organizations, including community health clinics, schools, and faith-based organizations. Since 1992, OASAS has issued biennial guidelines to communicate regulations, policies, and new research on substance abuse prevention to all contracted service providers as well as state and local government partners. The guidelines form the main part of OASAS’ contract requirements and are a critical component of the agency’s contracting, monitoring, and review processes for prevention services.

To increase the use of effective practices across the state, OASAS has set targets for the percentage of agency prevention funding dedicated to evidence-based programs and has embedded these requirements in its provider guidelines and contracts. In 2007, OASAS surveyed providers to establish a baseline of the percentage of funds going to evidence-based programs. Two years later, the agency updated its guidelines, which included a new requirement that provider organizations allocate an increasing percentage of their OASAS funding to the delivery of evidence-based programs and strategies. The agency has set a long-term target in which 70 percent of OASAS funds would be spent on evidence-based programs by 2018, allowing providers time to build capacity to reach the standard.

As part of their contracts, providers can choose from a list of pre-selected evidence-based programs. OASAS maintains a Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Strategies, which includes approved programs that have been rigorously evaluated and found effective. Providers can use the National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices that is operated by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Providers are also encouraged to submit proposals to elect promising practices for inclusion on the OASAS registry. A volunteer panel of prevention research reviewers meets biennially to review submissions (along with new and existing national or international research) to determine whether they meet the registry standards for inclusion.

“We don’t expect any of our providers to have 100 percent evidence-based programming. Every community is unique, and we provide prevention services to approximately 312,000 youths each year. With our provider guidelines, we wanted to provide direction and uphold high standards, but we don’t want a cookie-cutter approach.”

Arlene González-Sánchez, commissioner, New York Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services

To ensure that providers are complying with the key aspects of the guidelines, including delivering evidence-based programs and practices with fidelity to their original design, OASAS monitors their performance through multiple channels. For example, OASAS requires that all providers develop annual service work plans and helps them identify performance targets, which are used as monitoring benchmarks.

One performance standard requires that program participants attend at least 80 percent of evidence-based program sessions; this standard is a proxy for program fidelity, which is critical to evidence-based programs achieving expected outcomes. “We don’t expect any of our providers to have 100 percent evidence-based programming,” said Arlene González-Sánchez, commissioner of the New York Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services. “Every community is unique, and we provide prevention services to approximately 312,000 youths each year. With our provider guidelines, we wanted to provide direction and uphold high standards, but we don’t want a cookie-cutter approach.”7

New York’s investments in evidence-based programs have also contributed to better outcomes for the children and families they serve. For example, the state has seen a significant decline in tobacco and alcohol use by 12- to 17-year-olds. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the proportion of youths who smoke cigarettes decreased by approximately 40 percent from 2009-15, while the share of youths who consume alcohol decreased by almost 30 percent.8

Santa Cruz County, California

- Agency: Probation Department.

- Policy area: criminal justice.

- Number of providers: 14.

- Total funding for grants/contracts: approximately $2.4 million in state fiscal year 2015-16.

- Funding for evidence-based programs: 100 percent of providers receiving grant funding must offer evidence-based programming.

The Santa Cruz County, California, Department of Corrections recently rebid its contracts for community-based services for incarcerated adults to prioritize evidence-based programs. The Probation Department supports the county’s adult and juvenile courts by providing a continuum of services including pretrial assessments, probation, post-trial alternative custody, and juvenile detention. In December 2015, the Probation Department issued a request for letters of interest (LOI) from community organizations to provide evidence-based intervention and re-entry services related to implementation of the state’s landmark criminal justice reform effort, or Public Safety Realignment (A.B. 109). This reform transferred responsibility for more than 60,000 offenders to California’s 58 counties, thereby requiring county governments to develop facilities, policies, and programs to serve this population. In July 2016, the Santa Cruz County Probation Department began to select grantees and award contracts.

The additional funding made available through A.B. 109 enables the county to set high expectations for the types of services it will fund. In particular, the LOI guidelines note that the proposals “must demonstrate that programs and services to be implemented have been proven effective for the target population by multiple national research studies, and that they will be implemented to fidelity.” The guidance suggests that providers consult the Results First Clearinghouse database,9 which identifies hundreds of programs that have been rigorously evaluated by one or more of eight national clearinghouses. The letter also requires that service providers work with the Probation Department to develop a common set of outcome measures and report that information quarterly, along with submitting data for program evaluations and monitoring implementation to ensure fidelity.

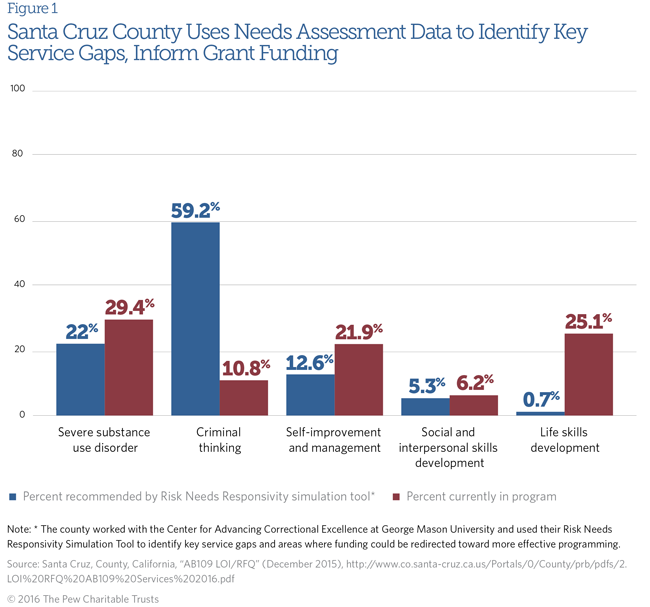

In developing the request for LOI, county staff used research and an analysis of local data to identify priority service areas to address the needs of the local A.B. 109 population. The county worked with the Center for Advancing Correctional Excellence at George Mason University to identify key service gaps and areas where funding could be redirected toward more effective programming. For example, the analysis found that the county lacked sufficient services, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, to target criminal thinking and behaviors, while too many organizations were providing life skills development such as career counseling.

The county is using prior data on service utilization and offender characteristics to determine funding levels for each of eight service types. (See Figure 1.) “We’re trying to get the most public safety gains possible from limited resources,” said Andrew Davis, senior departmental administrative analyst for the Probation Department. “We used to create programs based on best guesses and whatever we could find funding for. Now we’re in a position to build a network of services based on research.”10

Conclusion

The examples highlighted here demonstrate that governments can use contracting and grant-making processes as tools to increase the use of evidence-based programs in a wide range of policy areas. Over time, each jurisdiction has learned important lessons about the contracting process, including the need to educate and build support among provider organizations to use programs with demonstrated effectiveness. Administrators have also gained insights into the value of monitoring program implementation, particularly for interventions that require fidelity to a research-based model to be effective, and have built requirements and supports into their contracts to address this need. Finally, each government has made progress in balancing the need to deliver programs backed by strong research alongside the need to give providers flexibility in addressing the specific risk factors prevalent in their communities.

Endnotes

- Sarah L. Pettijohn and Elizabeth T. Boris, “Contracts and Grants between Nonprofits and Government,” Urban Institute, Brief #3 (December 2013), accessed July 21, 2016, http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412968-Contracts-and-Grants-between-Nonprofits-and-Government.pdf.

- A community needs assessment is a tool used to identify the resources available in a community to meet the needs of the population, including children, families, and disadvantaged groups.

- Georgia Division of Family and Children Services, Promoting Safe and Stable Families Program: FFY2017 Statement of Need (SoN), http://www.pssfnet.com/content/page.cfm/83/Funding%20Opportunities.

- Pew-MacArthur Results First interview with Carole Steele, director, Office of Prevention and Family Support, Georgia Division of Family and Children Services, May 6, 2016.

- Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, “JJIS Information,” accessed July 21, 2016, http://www.djj.state.fl.us/partners/data-integrity-jjis/jjis-information.

- Pew-MacArthur Results First interview with Amy Johnson, director, Office of Program Accountability, Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, May 5, 2016.

- Pew-MacArthur Results First interview with Arlene González-Sánchez, commissioner, New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services, Jan. 11, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “High School YRBS: New York 1997–2015 Results,” https://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/app/Results.aspx? TT=J&OUT=0&SID=HS&QID=QQ&LID=NY& YID=YY&LID2=&YID2=&COL=T& ROW1=N&ROW2=N& HT=QQ&LCT= LL& FS=S1&FR=R1&FG=G1& FSL=S1&FRL=R1& FGL=G1&PV=&TST=& C1=&C2=& QP=G&DP=1& VA=CI&CS=Y&SYID=& EYID=&SC=DEFAULT&SO=ASC.

- Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative, “The Results First Clearinghouse Database,” https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2014/09/results-first-clearinghouse-database.

- Pew-MacArthur Results First interview with Andrew Davis, senior departmental administrative analyst, Santa Cruz County Probation Department, California, May 12, 2015.

The Results First initiative, a project supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, authored this publication.

Key Information

Source

Results First™

Publication DateDecember 6, 2016

Read Time14 min

ComponentBudget Development

Resource TypeWritten Briefs

Results First Resources

Evidence-Based Policymaking Resource Center

Share This Page

LET’S STAY IN TOUCH

Join the Evidence-to-Impact Mailing List

Keep up to date with the latest resources, events, and news from the EIC.